Agricultural production, human population growth, and climate change have placed increased pressure on natural resources in French Polynesia. Local and global scale anthropogenic activities have impacted the health of fish stocks, coral reefs, and water quality of the islands, and threaten the ecosystem services they provide.

“Rāhui'' is a Tahitian term used to describe an integrated, community-based approach to natural resource conservation. Throughout the French Polynesian islands, Hawaii, and New Zealand, local communities have used various forms of rāhui for centuries to manage terrestrial ecosystems, preserve coral reefs and fisheries, and maintain water quality on land and in the surrounding lagoons. The exact definition and historical context of rāhui varies by place; the concept usually involves the strategic closure of an area to extractive activities or a moratorium on harvesting one of more species.

Rāhui can be applied to any natural or modified resource, including forests, plantations, shorelines, or lagoons. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, foreign researchers documented the use of this concept to protect environments across Oceana. For example, Tahitians used floating shrubs to demarcate a restricted area of the water, within which fishing or any type of resource exploitation was strictly prohibited.

In recent years, agricultural exports and international tourism have become central to economic development in French Polynesia. At the same time, local resource-users have struggled to maintain healthy ecosystems; fishermen and -women, in particular, have seen a sharp decrease in the productivity of once-thriving fisheries.

Hunter Lenihan, Professor of Marine and Fisheries Ecology at the Bren School, has been a leader of a long-term project dedicated to helping communities in French Polynesia re-apply the traditional rāhui system to terrestrial and marine ecosystems in the region. Lenihan is the co-director of the Rāhui Forum and Research Center (RFRC), an interdisciplinary team of ecologists, sociologists, linguistic anthropologists, and economists with the shared goal of long-term tropical resource and cultural conservation.

The RFRC was co-founded by Lenihan and Dr. Tamatoa Bambridge from the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS), in collaboration with the Island Research Center and Environmental Observatory (CRIOBE). From its inception in 2019, the Center’s aim has been to empower local communities to manage their natural resources by coupling participatory management strategies and contemporary ecological tools. They work with community leaders to 1) document and preserve traditional knowledge, 2) measure anthropogenic impacts and diagnose ecological problems, 3) model the effectiveness of different management scenarios, and 4) facilitate workshops and training sessions for local resource managers.

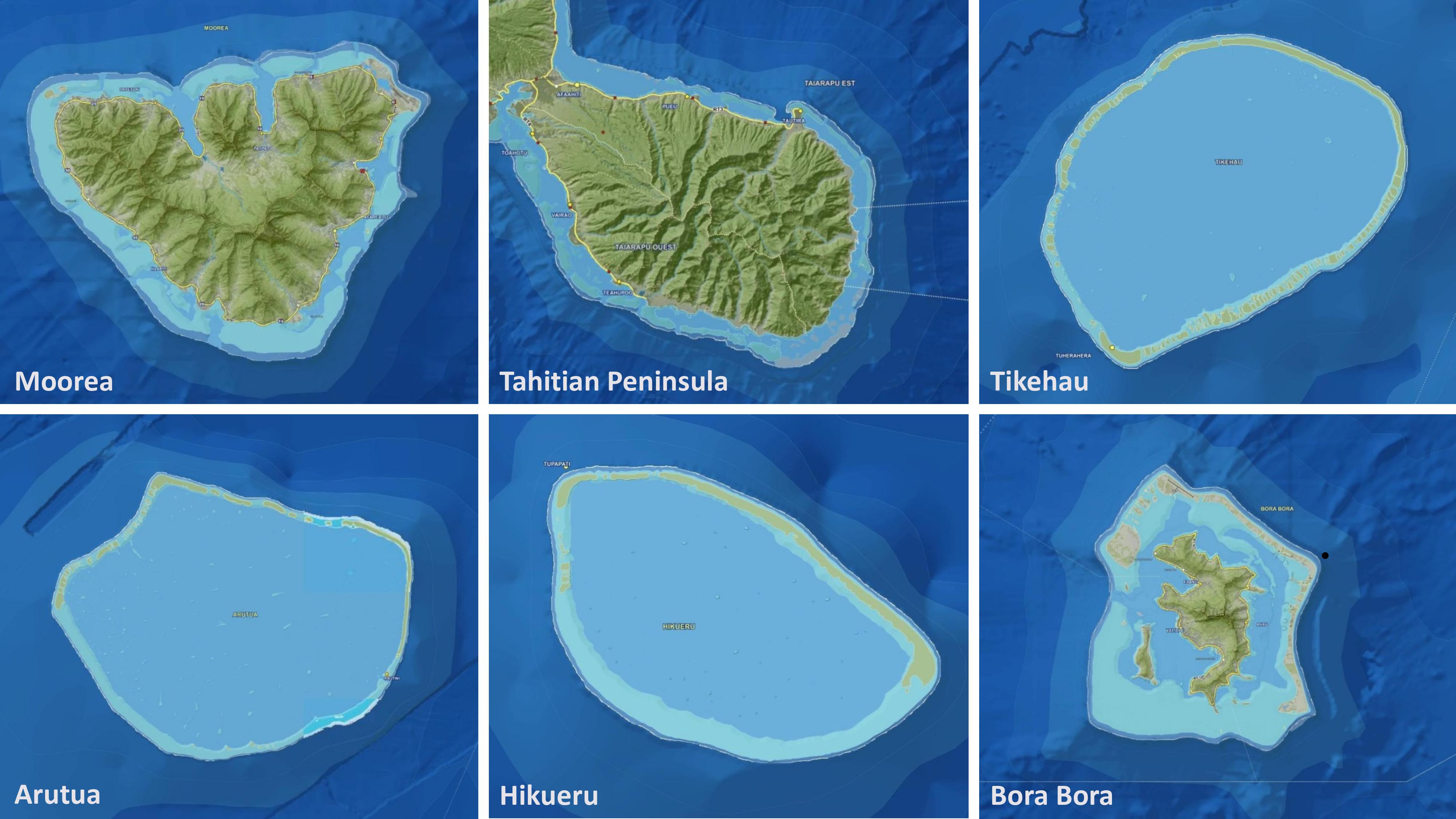

Together, the group has created distinct marine managed areas on 7 islands in the region: Arutua, Bora Bora, Hikueru, Moorea, Paea, Tikehau, and the Tahiti Peninsula.

Before the Center, previous efforts to create marine reserves in the area were heavily structured and implemented through a top-down approach, whereby a set of laws and regulations enacted by the government dictate how a resource can be legally harvested, disturbed, or consumed. In contrast, Lenihan notes that “Rahui starts within the community, it’s a bottom-up approach.” In addition, The Pew Foundation attempted to establish a set of reserves in the Austral Islands a decade ago but failed because they neglected to involve the national government.

An Integrated Approach

The process begins with a consultation between community members, researchers and the mayors of each island to identify specific conservation needs. The fundamental role of researchers is to provide support where it’s needed, rather than override or supersede the traditional management techniques or goals of the community. Collaboration with other community leaders, such as government officials, NGOs, spearfishing clubs, and members of the church, is key.

“Once the problem is identified by the community, we then provide a potential set of solutions. If there’s sediment loading in the river, for example, there are tools we suggest you consider to mitigate the situation.”

Interestingly, Lenihan stresses that one of the most important aspects of the collaboration lies between community members and linguists. Tahitian is a complex language with a rich oral history, and as with many dialects, specific Tahitian words and phrases are deeply tied to cultural identity and rooted in history. Subsequently, choosing terms to represent specific techniques and concepts surrounding natural resource management requires careful consideration.

“The choice of words in the Tahitian language is critical… Integrating linguistics into [this approach] gives it so much more power, more mana.”

Tahitian Concepts to Know

Many terms represent interrelated concepts, and are used in context with each other:

- Mana: “power from divine influence”

- Tapu: “the state of a person, thing, place or period where mana is present”

- Rāhui: “a form of tapu applied to a class of resources or to a territory” and “prohibition or restriction laid on hogs, fruit … by the chief”

Sources: 1) Davies, Jerbert John. A Tahitian and English Dictionary, with Introductory Remarks on the Polynesian Language, and a Short Grammar of the Tahitian Dialect. Jerbert John Davies. 2) Bambridge, Tamatoa. The Rāhui: Legal Pluralism in Polynesian Traditional Management of Resources and Territories. Anu Press, 2016.

Applying Rāhui to Fisheries

According to Lenihan, tackling issues related to fisheries management in French Polynesia is tricky. Regulatory power over fisheries is distributed across multiple government and non-government entities, yet top-down management strategies have been difficult to implement and enforce. Contemporary rāhui techniques may be part of the solution.

After local fishermen in Tikehau, a municipality in the Rangiroa atoll, began noticing that target species were becoming smaller in size, less abundant, and harder to catch, they reached out to the Rāhui Center for scientific support. Using spatial planning, researchers worked with the fishermen to define multiple geographic zones within which fishing is temporarily restricted. By relieving fishing pressure in one section of the lagoon, the hope is that this population will recover while fishing activities elsewhere continue.

To determine the efficacy of these closures, Lenihan and a team of ecologists are performing a series of surveys in each of Tikehau’s three restricted zones. The surveys are also helping the team assess “spillover” effects, a potential benefit of reserve systems that allows larvae from un-fished areas to settle in fished areas and increase populations.

Several other communities currently use adapted forms of traditional closure practices, like the one implemented in Tikehau, to manage fish stocks. However, temporary closures are only one piece of the puzzle. Long-term, the team hopes to implement size-based management techniques in the region, which establish strict size limits to ensure successful reproduction for fish populations.

In the case of fisheries, the ultimate goal is to couple size-based management and rotational closures to form an integrated solution for communities facing declining fish stocks. Rāhui are part of a broader concept of land-to-sea management that emphasizes the importance of looking at the entire ecosystem, instead of isolating one section or process.

Helpful Resources

Citations:

- Bambridge, Tamatoa. The Rahui: Legal Pluralism in Polynesian Traditional Management of Resources and Territories. Anu Press, 2016.

- Morrison, James. Journal de James Morrison, second maitre à bord de la Bounty. Musée de l’Homme, 1966.

- About Us | Rāhui Center. rahuicenter.pf/en/about-us/

About the author

Caitie Reza (MESM '22) is a Southern California native who enjoys writing, running, and exploring new places. Before coming to Santa Barbara to attend the Bren School, she spent time doing research in Arctic Alaska, Michigan, New Zealand, and most recently the middle of the North Pacific. Inspired by the people and creatures in the places she’s visited, Caitie hopes to continue studying threatened ecosystems and working closely with the stakeholders within them.