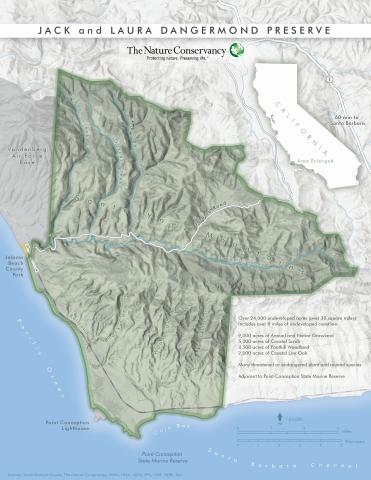

The nearly 25,000-acre Jack and Laura Dangermond Preserve at Point Conception is a singular place.

Located on the elbow of the California coast, this is where the cold-water currents of the northern Pacific mingle with the warmer waters of the Santa Barbara Channel and cattle ranches rub shoulders with celebrity compounds. Some call it the last perfect place in California.

The Chumash called the area home for more than 10,000 years before being forcibly removed by Spanish colonizers in the 1700s. Spanish missionaries lost ground to Americans in the late 1800s, and cattle rancher Bill Bixby bought the land in 1913.

As housing developments and freeways proliferated nearby, this vast stretch of coast stayed largely intact for a century, used only by grazing cattle, the Bixby family, and the occasional surfer. A hedge fund held the land, briefly, but decided not to develop. Locals and conservationists from all over the world breathed a collective sigh of relief when, in 2017, The Nature Conservancy (TNC) purchased the land, thanks to a $165-million philanthropic gift from tech entrepreneurs Jack and Laura Dangermond.

Now, the preserve is a safe haven for wildlife and a living laboratory for scientific research, environmental education, and cultural preservation.